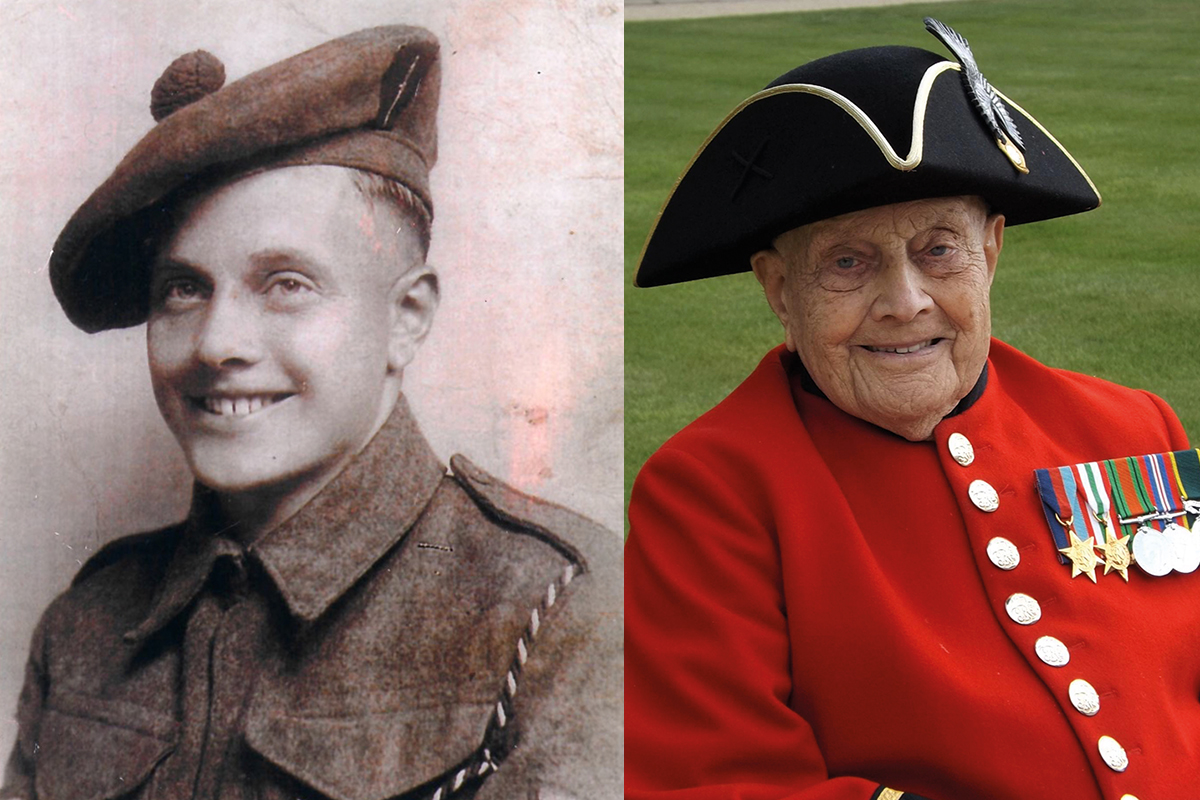

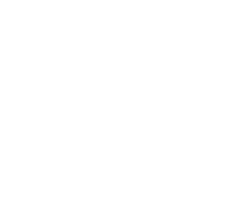

We have the honour of conducting the service of a true war hero George Parsons. Formally The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers then 2 Commando, a Minister and a Chelsea pensioner.

Here is his war story

I joined up in 1937, before the war. When I first got called up, I was bored, then things started to brew up a little bit and the Germans invaded Norway and the Lowlands. Churchill had to make some gesture and wanted volunteers for a rapid response unit. I put my name down on Saturday afternoon and on Sunday morning I was in Norway. I had a pretty rough time out there.

We landed at Oslo, five independent companies out of 10. Four went a little bit further north and number 5, which was my company, went down south.

“I remember thinking, what the hell am I doing here?”

About 100 miles down the road we did an ambush. We were at the bend of a road and first of all a detachment came along on bicycles, with rifles, laughing and joking. Then came motorcycles and cars and we still had no action. Then all hell let loose. I remember suddenly thinking, “A fortnight ago, I was a Saturday night soldier in South London. What the hell am I doing here? That chap over there and that chap over there are trying to kill me and I’m trying to kill them!”

All of a sudden, a shout came “‘Parsons! Parsons! You’re being surrounded. Get out as quick as you can!” There was a dip in the ground and we were pulling our packs along with our feet, bullets going over the top, until we got to a big chunk of rock where we got out safely and made our way back down on the road.

We had about four weeks without much to drink or eat. We thought it was hopeless trying to find the rest of the troops, as the Germans were too much in command there. So we decided to make our way back to the coast. We were given a fairly friendly welcome there and thought we could have some rest. Then a message came through from the Norwegians – there were Germans down on the towpath and we’d better move out. The best thing was to go up north, but we had no transport and someone told us we wouldn’t be able to go that way because paratroops had landed there and we’d be blocked off. That was the first time we’d heard of paratroops!

“We didn’t know we were in danger”

The only way was to try to get a boat. We went along the harbour and there was only one boat with a skipper still at the wheel. We said to him “Are you going?” and he said “No”. We were shouting up to the officer, “Why the hell won’t he get going?” and the officer said, “Apparently there’s a whirlpool up there”. We found out later it was the largest one in the world and it will take down a boat. They’d sounded the sirens, so no boat was allowed to move. We said, “Tell him to go – it’s only a bloomin’ excuse”. The officer said he wouldn’t go, so we said, “Put a bloody pistol in his back and make him go!”

In the end we went. We went across the whirlpool but at the time we didn’t know we were in danger. I went back later for a visit and met the grandchildren of the chap who was the skipper of that boat. They said, “It’s strange, Grandad always told us about those stupid English men, who put a pistol to his back and made him go over there! We all thought it was part of his folklore, but it was actually real!”

When we were put down, we made some enquiries and found out that our main unit was about 12 or 15 miles from the capital on the main road, so we were able to join up with them.

“There was only one house left standing”

I remember we started to settle in Fauske, but kept remote from the Norwegians for their own safety. Before the war, the Germans had what they call Quislings. These are people, German people, who go in and live in a village, then when the invasion comes they’ve got all the news, so you never know who you’re talking to.

One day, we went down the harbour patrolling and all of a sudden we’re looking up and there’s a sea plane coming over. The engine was spluttering and it landed out of sight round a bluff of rocks. We were very enthusiastic to catch a plane and their crew. As soon as we got in sight of them, up started his engine, he flew over and gave us a burst of machine gun fire but it didn’t hit any of us. We realised that was just a reconnaissance. Two days later it came over with high explosives. They told us afterwards that there was only one house left standing.

I’ll always remember we ushered about 50 or 60 children when the first bombs landed on these wooden structures. We put them in another building and were called away from there to the Swedish border. The last thing we saw was that house going up in flames. There was nothing we could do about it. I always wondered what happened to those children, but I don’t know.

“We were told, this is the last stand”

We were looking down, watching for the Germans to come and we were told this is the last stand. This is it. There was no darkness, just a dim light and we were watching them prepare and waiting for the onslaught. All of a sudden, they were loading boats. The tactic suddenly changed and they were moving out of there. The news came through that Norway had capitulated.

We were about nine miles over the Swedish border and had to somehow try and get home.

We hadn’t gone very far and they were coming down at rooftop level, machine gunning and bombing, and we thought, none of us will ever make this. So we decided to keep below the snow line and make great circuits, which was quite a long march. It took us about three weeks to the get back to the coast. We kept spread out, which caused a lot of tension with the Germans because they thought we were a larger force than we actually were.

Anyway, we finally got back to the coast and a battleship came in, but she had had a bit of a mauling and none of her guns were functioning. We were told, “If an air raid happens, we’re going to scoot out straight away”. We were lying low until there was some heavy bombing. Our little groups were given a number. Then when our number was called, we had a minute and a half to get up the gang plank, throw our rifle to the sailor at the top and get down below. That plan was successful despite the bombing.

We thought we were going home, but we were going up north to join back up with the foreign legion group. They wanted us to destroy the iron ore up in the north, which was very valuable to the Germans. It was about a two-day march which I’ll never forget, over mountain tracks and long roads. I would take my boots off and my socks and I was taking the flesh off my feet with it!

Luckily, the foreign legion had just completed their operation, so we didn’t really have much to do. After a pretty hazardous journey, we got back to the coast again and the boat came in. We thought we were going home, as everyone else had. But they said no and took us over to the Lofoten Islands, where there was a congregation of all nationalities. We waited there about a week and then we were shipped out mid ocean and a luxury liner came up – quite a famous one: the Lancastria. We were crowded in the cabins down below – clean and dry at last.

“The commando training was very intense”

We came back to Gourock in Scotland, where we heard the tragic news about Dunkirk. Churchill came and saw us and said, “Dunkirk is a tragedy and you’re really the only fighting unit that’s still compact”. He asked about our experiences in Norway and we told him we had a lot of trouble with paratroops. He said, “What are paratroops?” We said, “Oh they come in planes and drop people down”. He was rather amazed and said, “We’ve got nothing like that.”

Then he sent us up to Scotland for training because we were the only complete fighting unit. We said we’d do paratrooping, but Churchill said we were to stay with the beach landings instead. He said he’d recruit people for paratroops, which he did and that became the SAS.

We started training with live ammunition to make things more realistic. The commando training was very intense – you had to swim two lengths of the baths with fatigue dress on and a rifle and run two miles in 12 minutes. I was fit enough and enjoyed it, it was way out of the ordinary.

After a year mucking around with different titles we moved down to Paignton and they decided that something had to be more formalised and they formed us into commandos. I was no. 2 Commando under Colonel Newman.

“We were going to attack the underbelly of Europe”

Next we were moved out to Gibraltar. We were going to do the North African landing, but the Governor of Gibraltar was frightened the neutrality of Spain wouldn’t hold, so he wanted a detachment there so if they did come through Spain he had a force of people.

After that subsided, we went over to North Africa – a place called Phillipeville. We only did soldiering and that and weren’t involved much in the North African campaign, or the one that was coming in the other way. Looking back, I realised they knew when the two linked up we were going to attack the underbelly of Europe – we were there ready to join the forces.

After that, we moved on to Malta. It was during the siege and the blockade – a horrible time. What with the air raids and the blockades, you never knew when your next meal was coming.

“We nearly lost everybody at Monte Cassino”

Then the fortune changed and we moved to Sicily and then across to the toe of Italy. We made our way up north, along the West Coast, until we came across Monte Cassino. We tried to get back round to Salerno, but we nearly lost everybody there. We had to be rushed out to protect the bridge head, otherwise we would have lost our Army there. We stayed at Monte Cassino for quite a while, waiting for the final push – the weather was absolutely appalling.

When you are attacking a mountain path, like at Monte Cassino, you need the opposition to be about four times stronger than the defence. We never had the number of men to do that. Bordering it was the Pontine marshes where you couldn’t operate in tanks. It was such a commanded position, they could almost see what you had for breakfast! We were waiting for the final onslaught. There was the Garigliano – a very fast flowing river – and we were all braced up for going on the final assault on that. Then all of a sudden, when were on the verge of it, we were moved down to southern Italy again, where we were in the first place.

While we were in Italy the other commandos were preparing for D Day. One of the commandos that was out in Italy was called back to take part and the rest of us were left to go on to Naples. It was the Italian campaign that I was more concerned with.

Then we suddenly found out that were being sent across the Dalmatian Islands to a little island called Vis and from there to Yugoslavia, where we joined up with the Tito Forces.

“War was grim, but I’m glad I went through it”

Just as we were moving on to Albania, I had back trouble and was invalided back home to Scotland on compassionate grounds. It was getting near the end of the war. I was being rehabilitated and then the commandos were disbanded, because the war office didn’t like units like us because we had our own control.

I got the Italy star, the ‘39 and the war medal and, because I was in England, I got the defence medal and then the silver one with my name on it which was for 15 years of efficiency and good conduct.

War was grim, but I’m glad I went through it. I got exhilaration from the danger, but the best thing was the camaraderie. I’ve never had camaraderie like it since. It was terrific. I knew the chap on my right wouldn’t let me down and he knew the same.

The war bred a generation of men we haven’t had since. That bond can’t be replicated. It was a special bond. They were happy days, although dangerous.